Throughout its millennium-long history, Riga remained the main metropolis and trade center of East Baltic.

Medieval age: Crusaders to Merchants (until 1581)

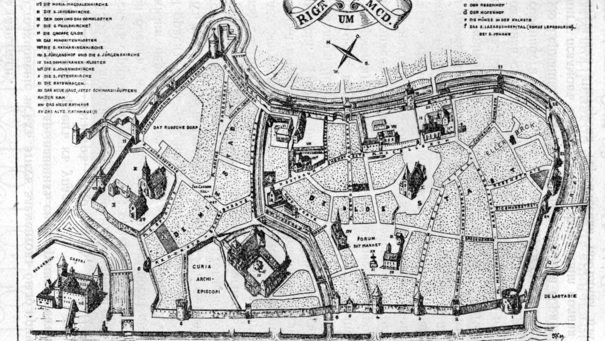

Riga’s location on the mouth of Daugava (Baltic region’s longest river) first came to prominence as a trade location in the Viking era. But the current city was founded German Christians in their fervor to Christianise the Balts, at the time Europe’s largest remaining pagan population. It became a bishop’s seat. Anchored in Riga, Christianity indeed soon prevailed over Latvia. Not everything was rosy, however, and the bishop of Riga often found himself fighting against the fellow Christians Livonian Knights who controlled areas south of Riga.

These conflicts were, however, pretty minor as the main Crusader forces moved southwards into still-pagan Lithuania. Surrounded by relative peace, Riga became a major Baltic trading city, part of the famous Hanseatic union. While its hinterland was inhabited by Latvians, the city itself was largely German (like many new Eastern European cities at the time). Germanic town law was adopted and its unique form known as Riga law evolved.

Where to see the era today? The main churches of Riga Old Town (Catholic and Lutheran Cathedrals) and some other key buildings there date to this era.

Foreign rule age: Poles, Lithuanians, Swedes and Russians (1581-1867)

When Lithuania Christianised in 1385, the crusading knights no longer had a reason to stay in the area. Still, they refused to leave. However, the tides of war were increasingly unfavorable for them and Riga fell to joint Polish-Lithuanian forces in 1581. The German city-state was replaced by a foreign rule, which would continue uninterrupted for over three centuries.

Poland-Lithuania lost Riga to Sweden in 1621 and Sweden had to relinquish it to Russia in 1710. However, Riga has never been a mere frontier outpost. In fact, it was the largest city in Sweden (surpassing Stockholm) and one of the largest cities in Russia. Regardless of the ruling great power, the economy remained in the hands of the local German community, the “Baltic Barons”. As late as 1867, German-speakers comprised 43% of Riga‘s population of 103 000 (Russian-speakers – 25%, Latvian-speakers – 24%). The local laws that made it impossible for non-Germans to become craftsmen, for example, stayed unrepealed for centuries after Germans have lost the political control of the city.

Where to see the era today? Much of the Riga Old Town dates to this era.

Golden age: Industrialization to Awakening (1867-1918)

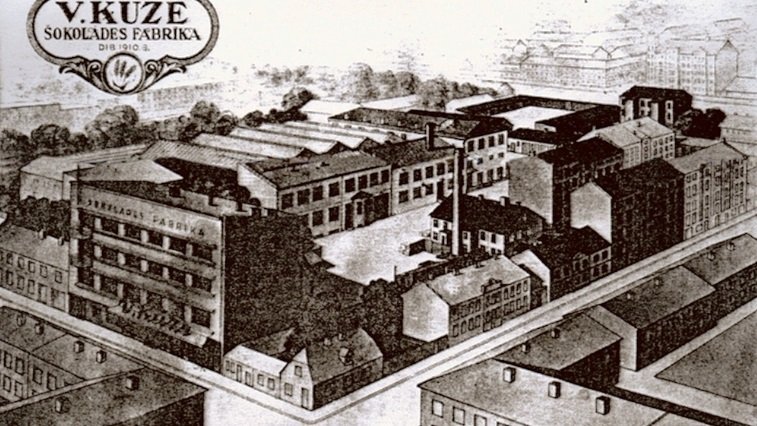

When a belated industrial era reached Russia, Riga became one of the Russian Empire’s largest industrial cities. Massive new districts of large buildings sprung up nearly overnight, hundreds of now-famous 5-6 floors art nouveau edifices were constructed filled with rental apartments. Exploding growth increased the population from 170 000 people in 1881 to nearly 600 000 in 1913. This number was much more impressive in that era than it is today as the cities generally used to be smaller.

As the center of a major region, Riga attracted so many people of other ethnicities that it had a larger number of Lithuanians than every city in Lithuania, for example (and even this meant just 7% of the total Riga population). Still, Latvians from villages were the majority of “new Rigans” and Riga more than ever became the heart of the Latvian nation, then undergoing a sweeping National Awakening. The Latvian-speakers share in total population increased from 24% in 1867 to 45% in 1897. At the same time, the German share declined from 43% to 22% as there were no rural Germans in Latvia who could participate in the urbanization.

Despite all this glory, Riga lacked political importance. All the major decisions were made in Saint Petersburg far north. Public signs in Riga were Russian rather than either Latvian (the local plurality language) or German (local elite language).

This was soon to change as World War 1 led to the defeats of both Russia and Germany.

Where to see the era today? As this was the prime era of Riga’s expansion it is not difficult to see. Centrs, districts east of Centrs, Maskavas suburb and Āgenskalns all were built to house new Rigans during the National Revival / Industrial revolution era. Sarkandaugava was the industrial heart of the times while Mežaparks hosted villas of the elite.

Freedom age: Capital of the nation (1918-1940)

With all the major empires weakened by war, Latvians seized the opportunity to crown their National Awakening with an independence declaration (1918). After a hard fight against various Russian forces (pro-czar Bermontians and the communist Bolsheviks), in 1918-1920 Latvians established a firm control over Riga and it was destined to become their capital.

The city lost a third of its people as many Russian officials went back to Russia while most Lithuanians and Poles moved to develop their own newly-independent homelands.

In 1935, Riga had 385 000 inhabitants, 63% of them ethnic Latvians. This was the only time in history Latvians were the majority of Rigans. German share stood at 10% and Russian share at 9%. Both of these minorities were surpassed by the Jews (11%) who arrived from towns (as the Russian Imperial limitations on Jewish settlement were scrapped by independent Latvia).

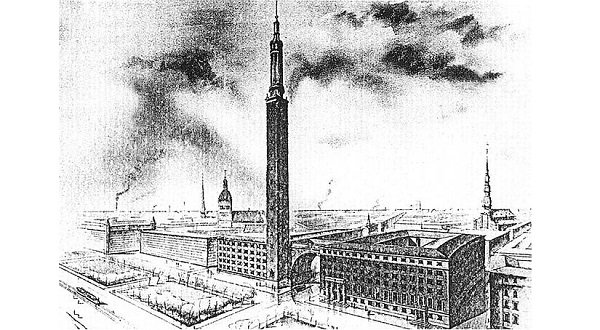

However, “The Paris of the Baltics” more than compensated its population decline by the power it had gained, attracting diplomats and celebrities, as well as undertaking major projects such as the Freedom fighters memorial and Skansen. Riga was destined to become a global city, but all the interwar glory was cut short by the Soviet Russian occupation in 1940: buildings were destroyed, grand projects canceled, and the ones responsible for building the Riga of 1930s were murdered.

Where to see the era today? Teika district is the only area of Riga built up during interwar independence era. The Soldiers memorial and Skansen near Mežaparks are some of the greatest projects of that era when the Latvian culture prevailed. Freedom statue near Centrs may look small but its symbolic value far outweighs its size.

Bloody age: Occupations to Genocides (1940-1990)

The Soviet occupation of Riga (1940) began as the “Year of Terror”. Tens of thousands Rigans were murdered or expelled to Siberia where further thousands perished. All the properties were nationalized and looted. Never before was Riga subjected to such brutality. The Soviet terror was so great that when Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, most Latvians greeted the Germans as liberators.

Not the Riga’s Jews, however, many of whom had collaborated with the Soviets. The Soviet genocide of Latvians was replaced by a new German genocide of Riga’s Jews (the majority of them either perished or fled).

In 1944-1945 the Soviets came back and the targets shifted back again. Not willing to wait for their death, many Latvian and German citizens of Riga evacuated to the West. Those who didn’t were to suffer a terrible fate.

The Riga German community was destroyed while the Latvian population severely reduced. Throughout the Soviet occupation, Russian settlers would be sent to live in Riga in the apartments that belonged to the Latvians, Germans or Jews recently killed or expelled. By the 1980s, Riga already had a Russian-majority, with Latvians making just 37% of the population. Even the Latvian language grew increasingly rare in public as ethnic Latvians had to communicate in Russian with the people of the other ethnicities (at that time, most neighbors and co-workers would have been non-Latvian). Two-thirds of Riga’s schools used Russian as the language of instruction, making Russian the primary language of most non-Latvian Riga’s kids.

The life itself in Riga was similar to that anywhere else in the Soviet Union with massive shortages of goods and long queues, extremely limited foreign travels, KGB surveillance and few entertainment opportunities. In the 1940s-1950s, massive Stalinist buildings were constructed in the downtown. In the 1960s-1980s, some concrete slab boroughs have been built in the West. However, Riga grew little: so many people perished in the genocides that even after the massive Soviet settlement Riga was not that much more populous than before World War 1. The population peaked at 910000 in 1989.

Where to see the era today? The Soviet pompousness may be seen in key edifices they built near the downtown, such as Stalinist Latvian Academy of Sciences in Maskavas suburb and the Soviet victory monument in Āgenskalns. The main residential expansion of Riga happened westwards as concrete slab districts such as Imanta were built; little has changed there after the Soviet times, save for construction of new shops. It is best to learn about the genocides and occupations at the Museum of Latvian occupation (Old Town) or the KGB museum (Centrs)

Modern age (1990 onwards)

In 1990, Latvia declared independence and Russian attempts to curb it failed as the Soviet Union totally collapsed. ~150 000 Russian settlers and officials moved out and Riga once again had a slight Latvian plurality (41% in 2000). Latvian became the sole official language for all the public inscriptions and advertisements but it took another decade before Latvian became the most common language you would hear in Riga streets. The communities remained bitterly divided. This was visible on many occasions, even at the World War 2 veteran commemoration, when ethnic Latvians would celebrate the Latvian Legion Day (anti-Soviet) while Russophones would celebrate the Soviet Victory Day.

Businesses brought international trends and ideas to Riga. At first, these companies were largely local but later foreign investments came in. The first modern skyscrapers were constructed in the 2000s.

After a difficult decade of transition (the 1990s), Riga reasserted its role as the “Capital of the Baltics” with the most representative offices of foreign corporations and embassies among the Baltic States, and the most destinations out of its international airport.

Where to see the era today? As the market economy returned in Latvia businessmen became keen to build over some of the empty or run down places that were skipped by the Soviet development despite being located at good locations. The western bank of Daugava (Āgenskalns near downtown) thus received its fair share of modern architecture, while shopping malls and supermarkets adorned key roads and district centers.

Thank you for this article, it is useful for my research!

Excelente! Muchas gracias por esta información

I am looking for birth information in 1900 in Latvia. I have no area just a name and date of birth. Could you tell me where I could contact the proper authorities. I know the lady died in 2013 in Canada but have no immigration record. Please can you help me?

I can’t imagine how awful it would have been to be forced to learn a foreign language in one’s own country.

I wish all Latvians prosperity, good health and every happiness for 2021

I think that you can search for information in the Latvia State Archive and Church books. It is possible to find information there up to the 16th century, but it takes time to find something.

At first, you can try searching here:

https://raduraksti.arhivi.lv/collections/1:4

Hi

I have been aware of Riga all my life, as my grandfather was, I believe, works manager of the Salamander Ironworks in Riga in the years before WW1. He was sent over from England to set up the factory and start production, and I have various photos of the ironworks. His name was Frank L. Berry, and I think him and his wife lived in Riga for quite a few years and found it a very welcoming place.

I’ve always wondered what became of the works, as my grandfather came back to England round about the outbreak of war.

Presumably the factory was demolished and is now a housing or industrial area. But it would be interesting to discover a bit more about the history of the Salamander Ironworks.

Can you help with any information?

Thanks

Bob

Hi,

The Latvian name of this was Rūpnīca “Salamandra”. You may Google it for some pictures.

Currently, Salamandras Iela (street) and surroundings are in the location. Apparently, there are still some ruins / abandoned buildings there.

Some information (in Latvian) is here, you may use Google Translate: https://lideruskola.lv/lv/raksti/lideris-roberts-hirss-un-vina-mantojums/ .

Thank you Augustinas. Interesting but not much about the Salamandra works itself. I will find my old photos and see if they look like what I have seen on these websites

By the way I live in Scotland

You are a mentally sick son of a bitсh, who is trying to reinvent history and spread fake information on the internet!

Mano tėvas prieš II pasaulinį karą mokėsi Rygos dailės akademijoje, 4 metus gyveno Rygoje, išmoko gerai kalbėti latviškai. Kur būtų galima gauti daugiau informacijos apie to meto Rygos dailės akademiją, jos studentus, veiklą ir kt.?