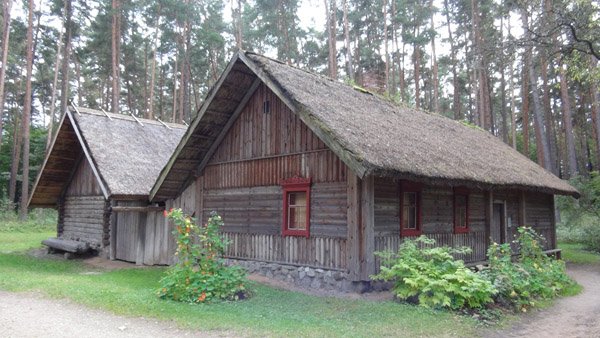

For centuries Latvia was a land of forests, and traditional Latvian architecture was wooden. Peasant homes were all built with architectural details that existed often meant to serve a practical purpose. Some of such homes still exist in villages and museums.

German knights who came to Christianize Latvia built the first cities, bringing with them brick buildings, Western European styles. Throughout the next centuries, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles influenced the key buildings of Latvia: castles, churches and townhouses. Baroque was especially influential in Eastern Latvia where Catholic faith prevailed as well as for palaces. Some of Latvia’s best known buildings are built in these styles.

The face of Latvia was changed by the 19th century urbanization. In building the new cities, larger than ever before, architects borrowed ideas from previous styles, firstly creating a Neo-Classical stule (imitating Antiquity) and then other Historicist styles (imitating every previous period). Cities have also received wooden buildings, ranging from simple apartment blocks of the workers to elaborate seaside villas for the rich.

By ~1900 the use of former architectural styles was replaced by an invented new one: the Art Nouveau. Riga is considered one of the most excellent repositories of Art Nouveau buildings, the Riga Art Nouveau falling into multiple substyles, one of them National Romantic which epitomized the Latvian national revival.

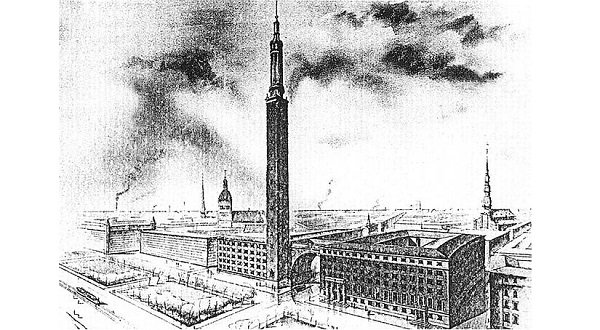

During the interwar independence Latvia lost population, limiting the architecture of the period to just a few districts in Riga. The few key projects of the era that were constructed were designed to epitomize the newly-born Latvia, showing that it is no more merely a province of some large empires. They borrowed on Art Deco and other then-popular styles.

The independence was cut short by a bloody Soviet occupation. In architecture, it started with rather impressive Soviet historicism (a.k.a. Stalinism, Socialist realism) as the only legal style. The style gave controversial buildings of gray/brown grandeur to Latvian downtowns.

It was however later (~1955) replaced by massive districts of cheap and nearly identical Soviet modernist apartment blocks. While often despised, Soviet modernism still forms the essence of many city districts.

After independence, Latvia constructed the buildings of once-neglected uses (e.g. Office blocks, shopping malls) using modern Western styles and materials, such as steel and glass.