Latvia is a multidenominational Christian nation.

Lutherans are its largest community, followed by 25%-35%. It predominates in the Western and Central Latvia.

Catholicism is the faith of 20%-25% of Latvia‘s inhabitants and the prime religion of Latgale (Eastern Latvia).

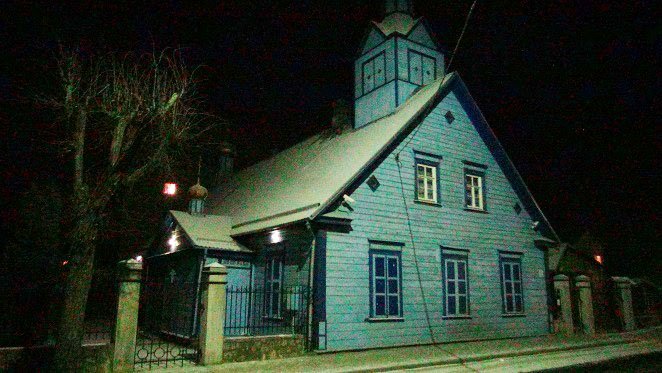

Russian Orthodox faith (18%-22%) is mostly followed by Russophone Soviet settlers and their descendants.

Old Believers (schismatic Orthodoxes who came as refugees to Latgale ~17th century) have ~1,7% as their followers.

There are many smaller, mainly protestant Christian denominations that are all together followed by 1,5%-2,5% of Latvia‘s population.

Largest non-Christian faiths are neo-Pagan Dievturi, Jewish and Muslim (in that order) but they are each followed by just 0,01%-0,05% of total population.

Under the Soviet occupation, atheism was promoted by the state, while the religious were discriminated against. This hit some communities more than others, with the Lutheran, Old Believers, and Jewish shares declining the most. In total, ~18% of Latvia‘s population is now irreligious.

Note that the Latvian censae do not record religion and the official statistics are based on self-reporting by religious organizations, which may use different systems to record the numbers of their followers. As such the percentages may have a big margin of error and vary among sources.