Latvia’s cities have nearly the same number of inhabitants today as they did 100 years ago. Because of this, most cities are dominated by old buildings and streets and there are relatively few dull modern buildings. Some cities, however, have been heavily damaged by World War 2 and Soviet destruction.

The cities of Latvia

There are three tiers of Latvia’s cities.

On the top tier is Riga alone. With 650 000 people, it is the largest metropolis in the Baltic States, surpassing Latvia’s second-largest city 7 times. Riga is the only true center of politics, business, and infrastructure and has more sights than the remaining cities combined.

The “second-tier” consists of regional centers with populations of 35 000 – 100 000 each. They serve as local shopping, entertainment, and infrastructure hubs. Each of them has enough sights for a 1-2 days visit. These cities are:

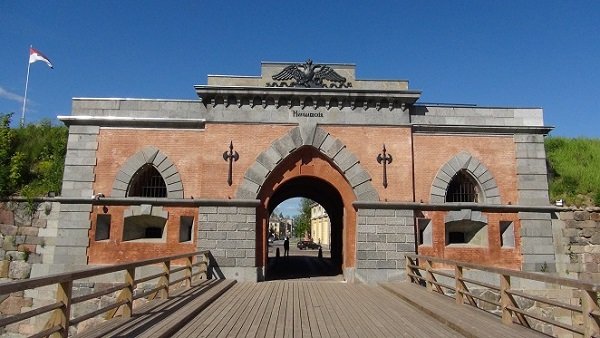

Daugavpils (pop. 93 000), the Russian-speaking hub of Latgale. It has an image of being poor and somewhat disloyal, but it has some sights such as the Russian Imperial fortress.

Liepāja (pop. 77 000) is Latvia’s westernmost city and one of its largest ports. Historically the port was even more important, and the entire derelict Russian Imperial 19th-century naval military city (Karosta) is a key attraction.

Jelgava (pop. 60 000) once served as the capital of Courland-Semigallia giving it a massive palace and nice churches.

Jūrmala (pop. 51 000), the Latvia’s top seaside resort and now effectively a suburb of Riga. Once separate fishing villages joined to become a single city, offering a long sandy beach and lots of summer entertainment.

Ventspils (pop. 39 000) is a historic port city in the northwest, famous for its well maintained old town, pretty landscaping and tourist-friendly attitude.

The third tier of Latvian cities (under 35 000 inhabittants) may have city status, but they are more correctly referred as towns. Some of the more historic towns, such as Kuldīga, Tālsi, Bauska and Cēsis have pretty old towns and other sights.

Districts and buildings

A Latvian city is often centered around a Medieval castle (ruined or repaired) or an 18th-19th century palace that housed the local overlords. Otherwise, the central square may be near one of the local churches. Due to religious diversity, there are usually many historic churches of different Christian denominations in a single city or town.

While a few cities (such as Riga) have extensive Medieval districts, in many others, ruined castles are among the only remaining buildings that old. The bulk of downtown buildings date to the urbanization era of the 19th century but they are none less pretty. Typical edifices of the era are apartment blocks, ranging from 2-floored wooden ones to elaborate historicist or art nouveau buildings dating to ~1900. Pretty natural areas that were once suburbs are full of well-decorated 19th-century villas standing amidst trees.

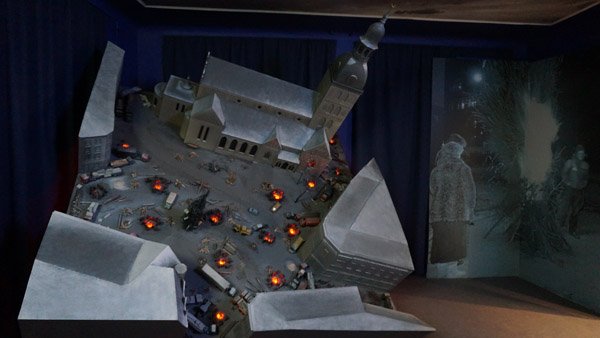

Depending on World War 2 and later damage, city downtowns may have some Soviet buildings. However, Soviet districts of dull and similar concrete slab buildings are mostly located beyond the downtown. They are smaller than in many ex-Soviet nations because the prime era of urbanization predated the Soviet occupation of Latvia.

Common post-independence buildings include shopping malls, which were built after the Soviet shortages ended and now serve as shopping hubs. Modern apartments and private buildings are other symbols of the new Latvian affluence.

More spiritual locations in every city are churches. The Russian Orthodox ones typically date to the 19th-century Russian Imperial era, Lutheran and Catholic ones may be both older and newer. The churches of Soviet districts are usually very recent, as their construction was banned during the Soviet occupation.

Another important site is the “Brotherly graves” (Brāļu kapi), which is a name given to the graves of soldiers who fell for Latvia in World War 1, World War 2 and the wars of independence. More controversial are graves of the Soviet occupational soldiers, which often become rallying sites for local Russophones.