Jūrmala, the Riga’s Seaside (1870-1918)

Jūrmala was a string of fishing villages well into 19th century. While some people would come here from Riga already in the 18th century, 25 km distance was too big for regular traffic in the era of horses and carriages.

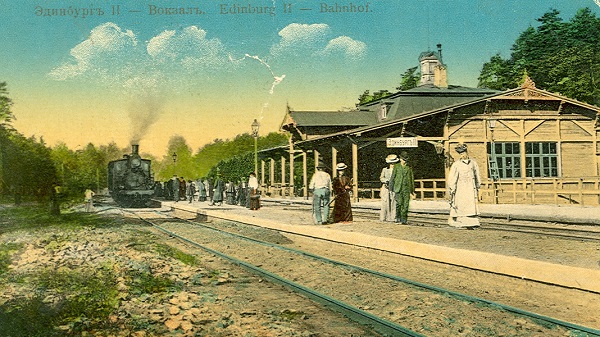

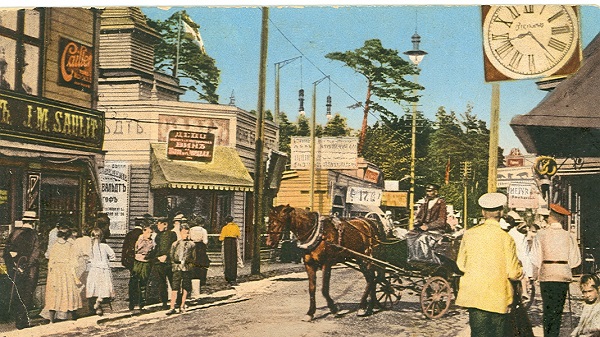

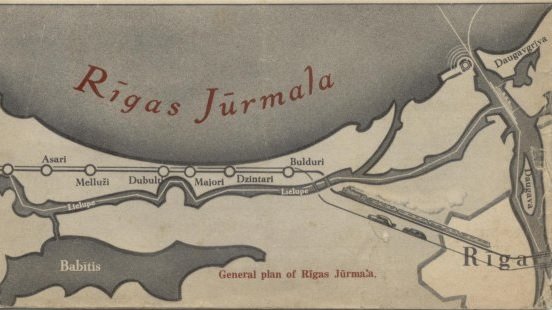

All that changed after the railway line from Riga to Tukums was completed in 1877. Each village received its own station where every warm summer day many holidaymakers from Riga would disembark, heading for the beaches. The villages closer to Riga then became known as “Rigas Jūrmala”, which means “Riga’s Seaside” in Latvian.

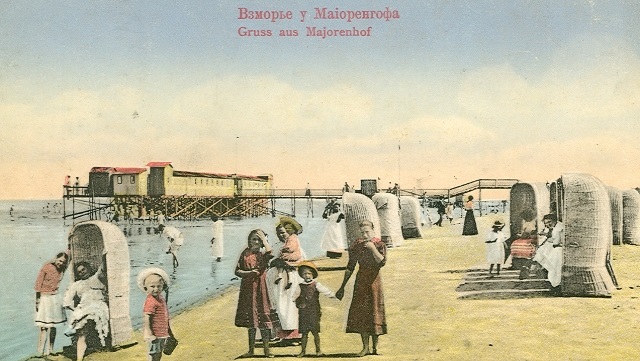

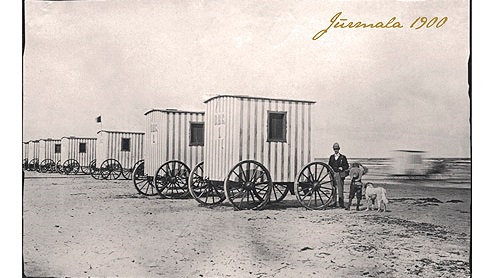

First major seaside buildings for tourists have been built, such as the Marienbade spa. The atmosphere of Jūrmala was more conservative then, with men and women swimming at separate hours until the 1890s, when the town became the first in Russian Empire to end segregated swimming.

Jūrmala expanded swiftly, with new straight streets laid amidst trees, all lined up by impressively decorated towered villas (mostly wooden) owned by the Riga’s elite (mainly ethnic Germans) as their “summer homes”. Small churches of various denominations, hotels, and restaurants were also built to cater for the tourists. The number of local inhabitants increased rapidly from 2000 in 1897 to 11000 in 1925.

Meanwhile, Ķemeri was not considered part of Riga’s Jūrmala (it was both too far from Riga and the coast), but it developed a tourist industry of its own, based around its mineral springs. In the 19th century, every nation developed such resorts as the craze of belief in impressive healing powers of mineral waters swept across Europe.

Jūrmala, the Interwar Latvia’s top resort (1918-1940)

After Latvia became independent in 1918 Jūrmala became its top resort. The government attempted to promote the area abroad as the “Baltic Riviera” with some success.

Ķemeri received a massive spa, one of the biggest interwar Latvia’s building projects. Dzintari concert hall has been built in 1936, becoming the hub of summer concerts ever since. Latvian names have been adopted for resorts that had German ones: Edinburg became Dzintari, Karlsbade became Melluži.

The population stood at 13000 in 1935 and 86% were ethnic Latvians.

Jūrmala, the Soviet Union’s Baltic Riviera (1940-1990)

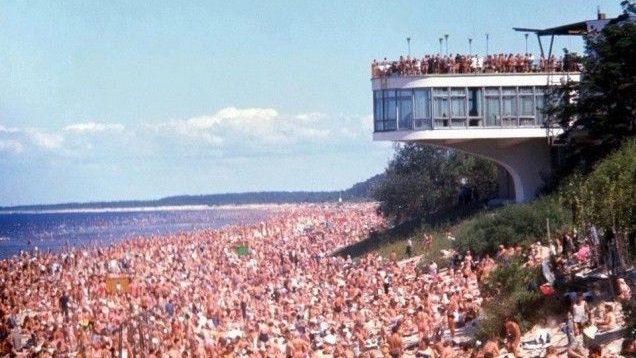

After Latvia was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940 many pretty villas and hotels were nationalized. Some were demolished, giving way to massive concrete sanitariums and hotels, but much of the “Old Jūrmala” remained and the city retained its charm. The numbers of tourists became larger than ever. The old “elite” atmosphere disappeared together with beach recliners, umbrellas, swimming cabins and much else. A Soviet beach was about squeezing in with your own mat for sunbathing, and this alone was no easy deal in unbelievably crowded summer weekends.

In 1959 the string of “villages” (including Ķemeri) was officially unified as Jūrmala city, becoming the Baltic Sea’s largest resort. “Riga” was dropped from its name, as the “Seaside” was not just Riga’s, but also entire Latvia’s or even Soviet Union’s. Despite its size, Soviet Union lacked year-round tropical resorts, so Jūrmala, imbibed in a more Western-feeling Latvian culture, became popular among Russians and Belarusians as well (260000 spent their holidays there in 1980). The local population was exploding as the Soviet Union would send in thousands of mostly Russian permanent inhabitants. Jūrmala had 14000 people in 1935, 38000 in 1959, 61000 in 1989. Latvian share declined from 86% in 1939 to 44% by 1989, nearly surpassed by Russians (42%).

Modern Jūrmala in free Latvia (1990-)

After Latvia restored its independence in 1990 the economic transition back to capitalism has changed the face of Jūrmala once again. New small private hotels and restaurants sprung up, often outcompeting the massive Soviet edifices, which in turn became abandoned. Tourism from the East declined both due to a difficult economic situation there and the visa regime. At the same time, Latvians were now allowed to spend holidays abroad – and the warm climate of Egypt or Turkey made it easy for these destinations to outcompete Jūrmala.

By the 2000s, however, Jūrmala regained some of what it had lost. While Latvians would continue to spend their holiday weeks abroad, many would visit Jūrmala on summer weekends. Tourists from ex-Soviet countries slowly returned, driven both by nostalgia, few cultural/linguistic barriers (Russian is still the most common second language) and Latvia’s economic miracle that made Jūrmala feel more advanced than whatever was available in Russia or Ukraine. In order to attract “Eastern tourists”, Jūrmala also hosted regular events such as the “New Wave” Russian pop music festival (2001-2014). In 2006 the city attracted 125000 longer-term holidaymakers.

Furthermore, Jūrmala firmly achieved the role of Riga’s suburb. Owning a car ceased to be a luxury and became a norm in Latvia, allowing many Rigans to move to Jūrmala and commute to downtown every day. This became especially popular among the middle class and the rich. Some have acquired dilapidated opulent buildings of 19th century Baltic Germans and brought them to new life, others built modern private edifices. Because of this trend, the population of Jūrmala did not fall as much as that of Riga itself, standing at 56 000 in 2011. Rigans moving to suburbs replaced some Russians who have left Latvia after independence (Russian share declined to 37% in 2000 with Latvian share increasing to 50%)

After Latvia joined the European Union in 2004 it began giving right of abode to everybody who owned an expensive real estate in Latvia. As the right of abode automatically allowed visa-free travel within the European Union, many rich Russians used up the opportunity to buy second homes in Jūrmala, thereby gaining both a place for summer vacations and a right to freely travel to Europe. This practice encouraged construction boom in Jūrmala and real estate prices skyrocketed.