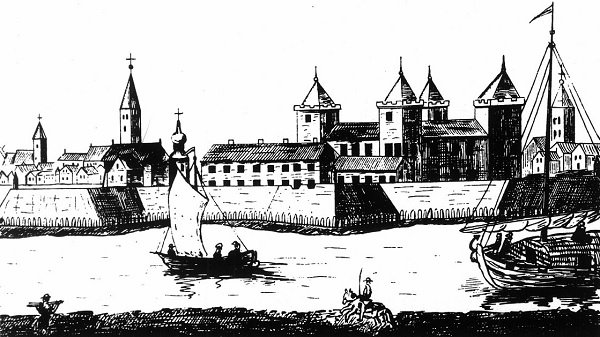

Southern castle of the Livonian Order (1266-1561)

While Jelgava has been inhabited by locals since at least the 10th century, it gained prominence only in 1266, when the local river island was used by the German Livonian Order to establish its castle (known as Mittau). The castle was then used to spread Christianity by force among the surrounding Baltic nations, including nearby Lithuanians. A town, known in German as Mittau, developed on the shores around the castle.

While the area did indeed became Christian, the Order was eventually defeated by a united Polish-Lithuanian force in 1561. It had to cede the majority of its lands and reform the remainder into a Duchy of Courland-Semigallia (a fief of Lithuania).

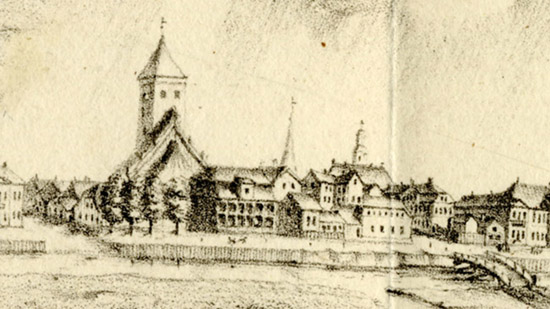

Capital of Courland-Semigallia colonial Empire (1561-1795)

Having lost the Riga metropolis, Courland-Semigallia chose Jelgava as its new capital, bringing new importance and expansion to the city. At its heyday in the 17th century, Duchy’s lands as far away as in America (Tobago) and Africa (Gambia) have been ruled from the Jelgava castle.

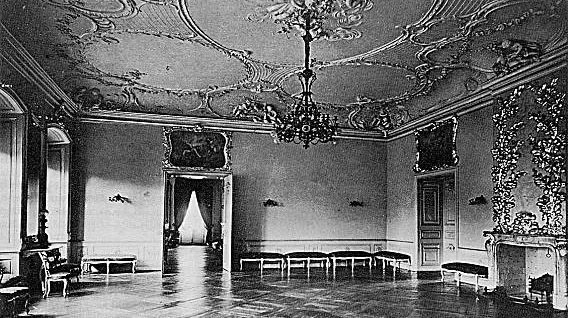

By the 18th century, the Duchy of Courland-Semigallia grew increasingly weak, devastated by numerous wars. You wouldn’t see that in Jelgava however, as it was also the time when the German dukes commissioned the city’s most opulent buildings: Jelgava Palace (1738) and Academia Petrina (1775). However, the palace was actually funded by Russian Empire as a mean to increase its influence over Courland-Semigallia. That influence eventually led to its demise.

Czar’s provincial palace to Latvian powerhouse (1795-1918)

In 1795 Russia have annexed the Courland-Semigallia completely, including Jelgava. The palace became just another property of Russian czars. In 1800s Russian czars lended it for use of the future French king Louis XVIII who was hiding there from revolutionary fervor in the France itself.

As industrialization belatedly reached the Russian Empire, Jelgava was transformed from just a “palace city” into a city of factories. A major impetus was the arrival of railroads: in 1868 the first line to Riga opened, followed by many other railways that elevated Jelgava into a major train transport hub (1873 – Liepāja line, 1904 – Krustpils/Daugavpils line and Tukums line, 1916 – Šiauliai/Vilnius line).

The city then saw many migrants from the villages, increasing both its population (from 23000 in 1863 to 35000 in 1897) and Latvian share therein (from 22% to 45% during the same timespan). Latvian National Awakening took full swing and Jelgava became the only city other than Riga to host the iconic National Song Festival (in 1895).

Jelgava’s proximity to Lithuania (also ruled by Russians at the time) allowed the city to double as a center for Lithuanian intellectuals in the late 19th century when Russian anti-Lithuanian policies effectively left Lithuania without higher education opportunities. The long-term interwar president of Lithuania Antanas Smetona (1926-1940) studied in Jelgava’s Academia Petrina.

Interwar Jelgava (1918-1940)

Latvian National Awakening culminated in the independence declaration in 1918. The country was invaded by various Russian forces who also occupied Jelgava, but they were all forced out.

As happened in all the Latvia’s cities, a large share of ethnic minorities left Jelgava, often to build their own homelands. Jelgava thus retained just 28000 population by 1925, 73% of them ethnic Latvians.

Like most cities, interwar prosperity allowed Jelgava to rebound. An agricultural university was established in Jelgava’s palace, creating the image of Jelgava as a student city. By 1935 the population increased to 34000.

Soviet occupation and devastation of Jelgava (1940-1990)

World War 2 has devastated Jelgava far more than most Latvian cities. The city has changed hands three times (occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, by Nazi Germany in 1941, and the Soviet Union again in 1944). In the process, some 90% of buildings were destroyed. The war also ravaged the local population as the local German community was destroyed in the Soviet Genocide while the local Jewish community was destroyed in the Holocaust (both stood at ~7% in 1935). Many Latvians were killed by the Soviets as well, while thousands of Russian settlers were moved in. By 1959 the city was 59,7% Latvian and 29,7% Russian.

After the death of Stalin, the worst totalitarianism has subsided. Jelgava was rebuilt in a nondescript style of concrete slab buildings, with only some iconic old edifices remaining as reminders of the Old Jelgava. Even many of them (such as Jelgava Palace) were actually gutted and have Soviet interiors.

Soviets-built numerous factories in Jelgava that worked for the entire union. One of the most famous was the RAF factory (constructed 1976) which was one of only two in the entire Soviet Union to produce small buses.

While the numbers of Russians continued to increase, Jelgava retained the highest percentage of ethnic Latvians among Latvia’s cities in the late Soviet era, falling under 50% only right before independence (49,7% in 1989).

Jelgava in independent Latvia (1990 and beyond)

Independence brought a resurgence of Latvian culture in Jelgava as the public signs were Latvianised and the Latvian share increased once again as some minorities have migrated away.

However, Jelgava’s economy was hit as the massive Soviet factories were horribly outdated and unable to compete in a free market. One after another they went out of business.

While neither Jelgava nor entire Latvia continued to produce its own automobiles after RAF made its final van in 1997, car ownership rates soared like never before. A luxury reserved for irregular journeys under the Soviet regime, cars became used for daily commute by everybody ~2000. This allowed Jelgava, located merely 46 km from downtown Riga, to feel increasingly like a Riga suburb, allowing it to get a share of the growth that has been happening in the capital.