Daugavpils, also known as Dinaburg (German), Dvinsk (Russian) and Daugpilis (Lithuanian) had a turbulent history of rapid population growths and declines. All the major increases took place under foreign regimes due to non-Latvian newcomers, while each regime change would have sent the population down as people of ethnicities associated with the previous regime would leave for their homelands.

Russian Imperial Daugavpils and its end (1810-1944)

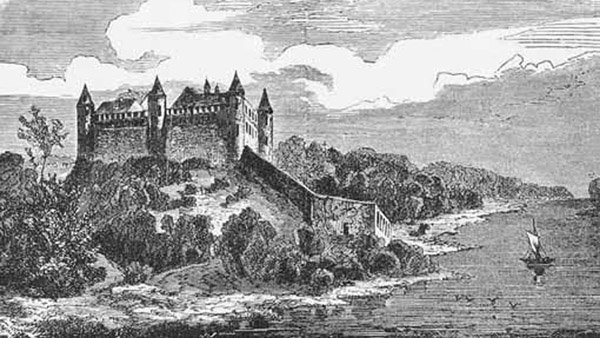

The first growth of Daugavpils took place under Russian Imperial regime when the Empire constructed a fortress here (1810-1878) while businessmen established industry in what was a major rail junction on Saint Petersburg-Warsaw line (laid in 1860).

The city increased in size from 3000 in 1825 to 113000 in 1914 mainly because of migrants from the rest of Russian Empire. Many were Russians but even more were Jews as Daugavpils was one of the few Imperial cities where Jews were permitted to freely settle. As such, it has gained a Jewish plurality (47%).

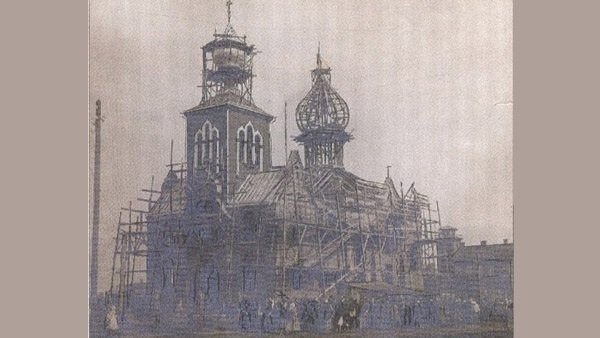

By 1897 merely 2% of locals were ethnic Latvians, surpassed also by Russian settlers (30%) and Poles (16%) who came from Latgalian towns (where they had strong communities since the area was ruled by Poland-Lithuania in 16th-18th centuries). Daugavpils downtown was built up with red brick buildings around straight streets, while each religious community erected its own temples, creating an iconic “Churches hill” where prayers would have resounded in a multitude of languages every day. Each ethnicity even had its own name for the city: to Russians, it was Dvinsk, to Jews – Dineburg.

After World War 1 and Latvian independence (1918), many non-Latvian inhabitants have left Daugavpils and its population declined to 51000 in 1935. Daugavpils lost the title of Latvia’s second largest city to Liepāja. Ethnic Latvians now made a plurality (34%), but the city continued to be shared by four main ethnic groups (25% Jews, 20% Russians, 18% Poles).

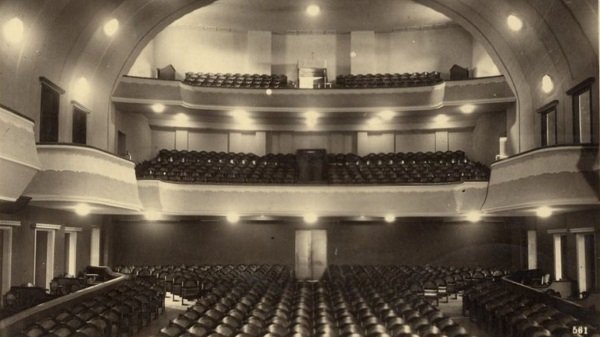

As a hub of Eastern Latvia, Daugavpils received a fair share of development, such as the massive Unity House with halls for theater and concerts.

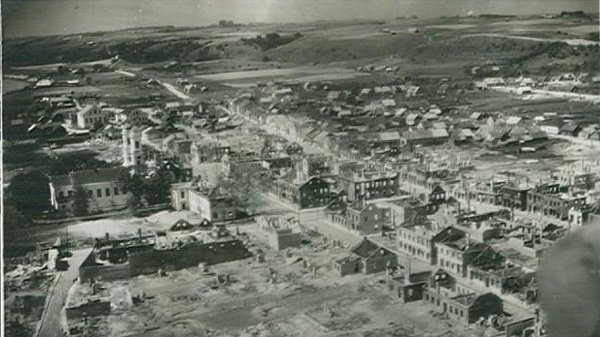

Perhaps Daugavpils would have been slowly transformed into a Latvian city but that was not to be. World War 2 occupations proved to be a major upheaval that put a final nail in the coffin of that 19th-century city, destroying the majority of its buildings and people. It is often claimed that by late 1940s merely 20000 people remained in the city, wiping out the population growth of past 70 years.

Soviet Daugavpils and its end (1944-)

In the place of old Daugavpils Soviets essentially constructed a new city after 1944. Historic Downtown buildings were often replaced by Soviet ones (Stalinist grandeur in the 1950s, shabby edifices later). Many former districts were turned into empty fields with propaganda sculptures.

Soviets have also sent in thousands of settlers from Russia to repopulate Daugavpils after World War 2, launching the second major period of population growth. By 1959 Daugavpils had 65000 inhabitants. For the first time in its urban history, it had a single majority ethnicity: Russians (55,9%). Latvians now made just 13,2% of locals, Jews – merely 3,4%, both declines a testament to World War 2 genocides.

While the Polish community seemingly remained strong (18,4%) such strength was superficial. Like all the ethnic minorities of Soviet Latvia (Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians), Poles of Daugavpils were slowly Russified. There was close to no media, education, culture or entertainment available in any language besides Russian, so parents ceased to teach their children the “useless” ethnic languages. By 1989 only about a quarter of these minorities still spoke “their own” languages, most of them elderly.

As such, the Soviet Daugavpils (unlike the Russian Imperial Daugavpils before it) was not really a multicultural city. Rather, it became a city of a single (Russian) language and arguably a single religion (atheism).

So, Daugavpils was a utopia to Russian communists: a location where a single Soviet nation was almost born. But it was also a dystopia to most Latvians: a reminder of what all Latvia could become, should the Soviet occupation and state-sponsored Russian immigration continue.

These fears helped reignite the pro-independence movement in the late 1980s. While Daugavpils did not participate in it that actively, many of its Russians and Poles were also fed up with the economically backward militarist Soviet regime, coming to believe that maybe independent democratic Latvia would do better. In 1991 referendum on Latvia’s independence thus only a quarter of Daugavpils residents have actually voted “Against”.

Many of those likely left Daugavpils soon afterward, as the city population declined from its peak of 125000 in 1989 to 115000 in 2000.

However, unlike elsewhere in Latvia, Russians retained the majority (54%) and the city remained Russian-speaking, many of its inhabitants refusing to learn Latvian. In independent Latvia where Latvian slowly replaced Russian as lingua franca, this became a hindrance. In addition to direct disadvantages, the Soviet settlers who spoke no Latvian received no citizenship, rendering a third of Daugavpils inhabitants stateless.

Perhaps due to all this Daugavpils became visibly poorer than other Latvian cities in the 1990s and early 2000s, its iconic fortress turned into a kind of tamed slum for the poor people. In the mid-2000s however, as Latvia’s spectacular growth increasingly went beyond Riga, Daugavpils also received modern malls and downtown renovations.

Still, the non-Latvians of Daugavpils grew increasingly disillusioned with independent Latvia, while ethnic Latvians increasingly saw Daugavpils as disloyal. Both facts were epitomized in two referendums when Daugavpils became the sole large Latvia’s city to vote against European Union membership (2003) and for an official status to the Russian language (2012). To many ethnic Latvians this (especially the 2012 proposition) amounted to treason, an attempt to “turn back the time” and “turn Latvia towards Russia”. For the Russian-speaking population of Daugavpils however, modern post-Soviet Russia may often seem to be a much more understandable and culturally acceptable place than either Latvia or the European Union.

Now that’s one Russia-centric article. Ignoring everything but the bits of history related to Russia and Soviets. Even the first 500 years of the city are just simply skipped.

I would like to ask what is the origin of the picture of the 19th Century train station.

I would like to use it in an article about the history of Daugavpils.

Thank you.

I don’t really remember it by this time, but the images of that age should already be in the public domain, and thus I posted it freely. You may try to do a Google reverse search for image.

9oce9q

866lpb